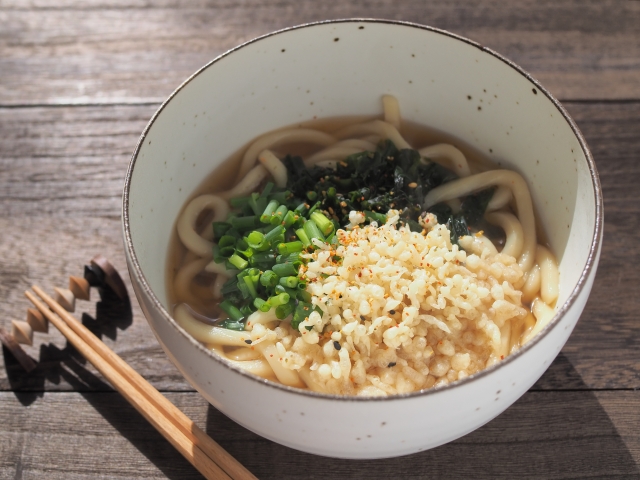

Dashi is the foundation of Japanese cuisine, providing a rich umami flavor that enhances the taste of various dishes. It is an essential ingredient in miso soup, simmered dishes, hot pots, and noodle broths.

Nutritional Benefits

Dashi is packed with naturally occurring umami compounds like glutamic acid (from kombu) and inosinic acid (from katsuobushi). These components not only enhance flavor but also aid digestion and overall well-being.

Types of Dashi

Kombu Dashi: Made by steeping dried kelp from Hokkaido, producing a clean, umami-rich broth.

Katsuobushi Dashi: A flavorful and aromatic broth made with dried bonito flakes.

Niboshi Dashi: Made from dried sardines (niboshi), offering a strong fish flavor.

Shiitake Dashi: A vegetarian broth made by soaking dried shiitake mushrooms, providing deep umami.

Awase Dashi (Blended Dashi): A combination of kombu and katsuobushi, commonly used in Japanese cooking.

Uses of Dashi

Miso soup is the base for Japan’s most iconic soup.

Enhances the flavors of vegetables, fish, and meat.

Forms a flavorful broth for winter hot pot dishes.

Adds umami to rice dishes.

How Dashi is Made

Kombu Dashi: Soak kombu in water, then slowly heat and remove it just before boiling.

Katsuobushi Dashi: Add katsuobushi to boiling water, let it steep for a few minutes, then strain.

Awase Dashi: First, extract kombu dashi, then add katsuobushi for extra depth of flavor.

Convenient Dashi for Home Cooking

While traditional dashi-making is ideal, many households use “Hondashi” or instant dashi granules for convenience. These pre-made options dissolve easily in hot water, making it simple to prepare miso soup, simmered dishes, and more.

History of Dashi

The tradition of making dashi dates back to the Nara period (710–794), when people began extracting umami from dried seafood and kelp. In the Muromachi period (1336–1573), katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) became widely used, and by the Edo period (1603–1868), the modern method of making dashi was established. Concepts like “ichiban dashi” (first brew) and “niban dashi” (second brew) were refined during this time, forming the basis of Japanese culinary techniques.

Comments